"Great hunter" catches DKK 60 million for a new Arctic basic research centre

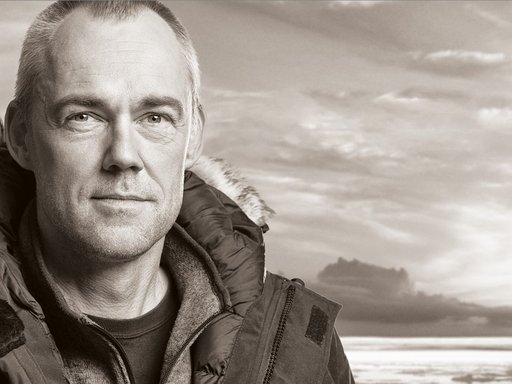

Professor Søren Rysgaard has received funding for a new basic research centre at Aarhus University to determine how coastal waters in the Arctic are changing as a result of climate change. The grant is a major academic recognition and perhaps the crowning achievement in a remarkable career in Arctic research.

After a rather turbulent flight, the helicopter prepares to land at the small heliport on Disko Island. The weather is clear, and out the window we see a 2.03 metre tall man running across the frozen lake to the heliport. Right up to the point where all 2.03 metres disappear through the ice.

The rotor is extremely loud and makes a half turn so that the hole in the lake is out of sight. A huge cloud of dust envelops us before the pilot touches the wheels to the ground.

When we finally open the door, the 2.03 metre tall, dripping wet man is standing next to the heliport with a huge smile. A completely soaked Søren Rysgaard welcomes us to Disko.

On the rocks along the road to the Arctic station, locals are laughing heartily as only Greenlanders can laugh, while Søren Rysgaard leaves a wet trail behind him. They've seen the entire show from the front row.

"Piniartorsuaq," they shout, laughing.

It means something like 'the great catcher' or 'the great hunter'.

Drawn to nature and the Arctic

Growing up in Snedsted in Thy, Søren became good friends with Thomas Rasmussen. And they weren't very old before the two of them set off on long hikes with their backpacks or canoe trips on the many small rivers.

And they both dreamed of travelling north. As far north as possible. After HF, Søren left for Iceland, but he only had enough money for a one-way ticket. There, Søren tended to cows, sheep and horses until the day he fell off a horse and broke his arm.

Back from Iceland, Søren got a job at the refugee centre in Agger, where refugees from Iran and Iraq were flooding in. It was a life surrounded by PTSD and short fuses, where knives and tools were often confiscated in the kitchen. But Søren won everyone's hearts. Whether it was the general's son or a humble freedom fighter, his height and straightforwardness calmed tempers.

He also spent time at a kibbutz in Israel, and had Søren's mother not pushed for him to get an education, he would probably still be travelling around today.

Søren started studying biology at the University of Copenhagen. The study place later moved to Aarhus University, where Søren first handed in an impressive and quite comprehensive master’s thesis and later, in 1995, handed in 18 scientific articles for his PhD thesis. Work that had the scope of a doctoral dissertation. But as Søren says: "A doctoral dissertation is something you can write when you retire".

While Søren was roaming around at university, Thomas joined the Sirius Dog Sled Patrol, based in Daneborg in North-East Greenland. And here, he saw a unique Arctic nature that he wanted to show his old friend.

A month alone in a small trapper's hut in North-East Greenland

With a grant of DKK 80,000 from the Carlsberg Foundation, Søren managed to go to Daneborg in 1994. He brought with him the very experienced laboratory technician, Preben Sørensen, from what was then called the 'Department of Genetics and Ecology', more commonly known as the 'mud passage'.

Søren and Preben worked from a very primitive hunting station, Sandodden, with no water or toilet facilities, which Danish trappers had used for hunting in the area primarily in the 1930s and 40s. The hut's so-called porch was set up as a 'laboratory', and the snowdrifts outside the hut were transformed into 'incubators' with different light and temperature conditions.

After a month of hard work, they had samples and data that could unlock the first secrets about the nutrient turnover of an Arctic seabed, where the temperature is minus 1.8 degrees Celsius all year round.

This resulted in two international publications. And from there, the snowball in Arctic research was on a roll - and eventually became an avalanche. Young Sund in North East Greenland was put on the world map

The old weather station

EU funding was added, and from 1996 onwards Søren gathered many Danish and foreign researchers for fieldwork in Young Sund.

Accommodations were in the old weather station, 'Kystens Perle' (The Pearl of the Coast). The station was vacated way back in the summer of 1975. The coffee cups were still on the tables and the stench of dried fish - used for dog food - hung in the air when researchers moved into the rather dilapidated weather station in 1996.

Accommodation was in bunk beds with four bunks in each room, and cooking was done with Trangia (storm kitchen with alcohol burner) in the early days. Toilets and showers were only in your dreams. And for some reason, everyone was smoking a pipe. Because there were ONLY men. And the air was thick in the small rooms.

Everything was transported far out on the ice on small sledges. This included large equipment, scuba tanks, tents, you name it. The draught animals in front of the sledges were the researchers, and it was a long way back to the weather station when you forgot something.

Work was done around the clock, as it was as bright at night as it was during the day. Ronnie Glud, who is now a professor at the University of Southern Denmark and used to working at all hours of the day, said late one night: "You always have the taste of blood in your mouth when you work with Søren."

Over the next few years, miracles happened: A gas cooker was added - and even a gas heater so you could occasionally take short baths. Water came from a nearby lake that was not frozen solid. Walls were torn down to create a small kitchen-dining room and a primitive laboratory.

The pioneering spirit flourished, creating great vibes and valuable collaborations across institutions and countries.

More and more people heard about the activities in North-East Greenland, and more and more people wanted to visit the remote location.

Among them, the chair and vice chair of the Aage V. Jensen Foundation, Leif Skov and Niels Skov, who focus on initiatives in Greenland.

Søren sneered at these VIP visits.

"We don't have time to show such tourists around," he proclaimed, sailing out into the fjord to take samples during the foundation's visit.

But the 'tourists' in this case fell head over heels for the cowboy who made things happen and prioritised hard work over pandering to influential politicians and foundations.

Funds then began to flow to marine research at Daneborg, where the Aage V. Jensen Foundation financed both a boat and a new, habitable field station.

Professorships in Nuuk, Manitoba and Aarhus

In 2005, the Aage V. Jensen Foundation donated funds for a professorship at the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources, for which the foundation had previously financed the building.

Naturally, Søren Rysgaard got the professorship, and over the next seven years he established the Greenland Climate Research Centre with a large research group.

But Canada also heard about the Arctic whirlwind, and the University of Manitoba offered Søren the highly prestigious position of 'Canada Excellence Research Chair'.

"When I come across a mystery, I want to solve it," was Søren's apt remark when he was introduced to all of Canada.

The position also came with a lot of research funding and collaboration with a large Canadian research group.

Alongside all the activities in Canada and Greenland, Aarhus University established the Arctic Research Centre (ARC) in 2012, where Søren became centre director, and in continuation of this, Søren initiated a research collaboration across the three countries with the Arctic Science Partnership, which has since expanded to include several countries and research institutions.

Over the years, he has met countless influential people and has personally told the then Prime Minister, Lars Løkke Rasmussen, and the then US Secretary of State, John Karry, about the effects of climate change.

Many whispered in Søren's ear that he should probably get a suit to wear to the many public events. He simply refused to spend money on it until his manager at the Nature Institute in Nuuk suggested he buy it under the category 'field clothing'.

Jutlandic humility

Not many people would call Søren Rysgaard a great diplomat, but he has been able to open doors and create alliances among research institutions, business, the military and many others that few would have seen coming.

He couldn't care less about titles and positions. But he knows who he can count on and who delivers.

And then there's his Jutlandic humility. And he'll probably hate this publicity....

He has supervised countless master's and PhD students, all of whom have benefited from a visionary and diligent supervisor who literally leads the way on all fronts. Søren is the one who fixes the boat engines, stands in the kitchen, ties the right knots on the boats and works in the lab if necessary. More importantly, he is able to see the people he works with and provide social care.

Did I mention that over the years there have also been six children - with the same wife? To whom he is still married. Truly a further achievement. Not least by the wife.

Søren Rysgaard has, like few others, managed to turn on the high beam and see goals out there in the distance that may not have been obvious to others.

Now the great hunter has also caught a basic research centre in fierce competition with the country's other sharp research minds. The next 6-10 years will - also - charge ahead at full speed.

Read the news about the new basic research centre for Ice-free Arctic Research (CIFAR) here: https://nat.au.dk/en/about-the-faculty/news/show/artikel/nyt-center-undersoeger-konsekvenserne-af-smeltende-is-og-mere-ferskvand-i-arktis

Peter Bondo Christensen, senior researcher at the Department of Ecoscience, Aarhus University, is a former thesis and PhD supervisor for Søren Rysgaard and has participated in several of the research field trips in Greenland.