The little auk - a major engineer

New research, carried out by a team of researchers from Arctic Research Centre, Aarhus University, shows that a very small bird, the little auk (søkonge), has a very large effect on both freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems in the remote Arctic region.

Little Auks gathering on the stones before descending into their nests or before setting out to sea to feed and collect food for their young. (Photo: S. Wetterich)

The little auk is the most numerous seabird in the North Atlantic and an estimated 30 million pairs travel to the North Water Polynya (NOW) to breed each summer.

The birds feed at sea on lipid rich copepods and transport large quantities of nutrients to their breeding colonies. The effects of this transport can be clearly seen in the landscape. Areas outside bird colonies are barren with little vegetation, as is expected at 76º North, whereas areas within bird colonies have lush vegetation and large numbers of grazers such as muskox and geese.

The study, published today in the Proceedings of the Royal Society - B combined limnology, aquatic ecology, isotope biochemistry and bird tracking methods in the NOW. The study is part of the large interdisciplinary NOW-project (now.ku.dk) with anthropologist, archaeologists and local Inuit hunters funded by the Carlsberg and Velux foundations.

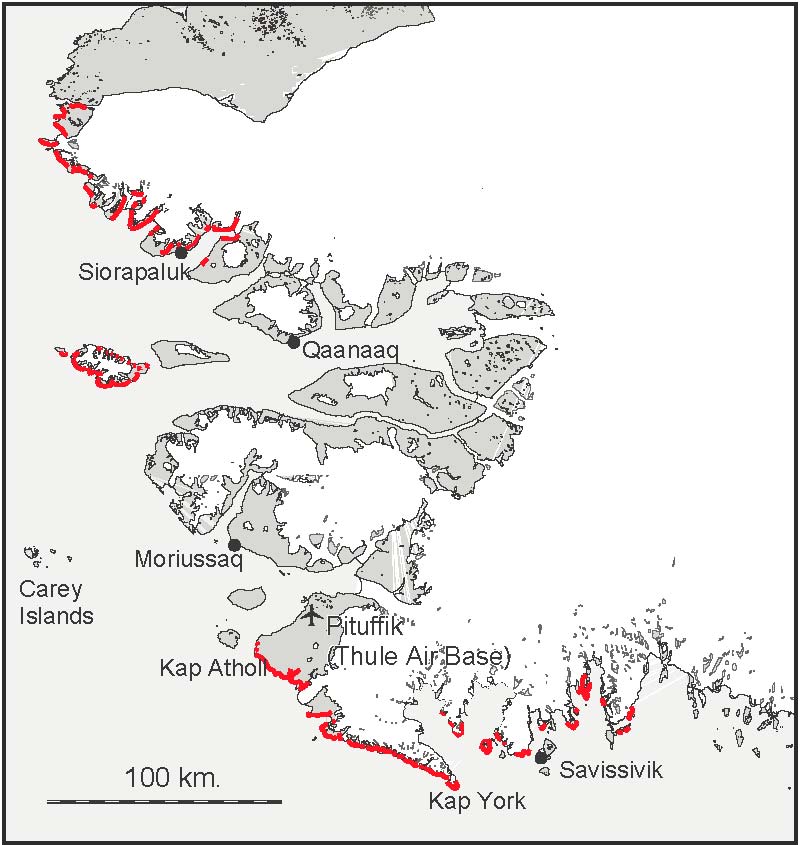

“On a broad scale we sampled over 30 locations, both with and without bird colonies along the 400km coastline of the NOW, from Savissivik in the south to Siorapaluk in the north and demonstrated that both aquatic and terrestrial productivity is much higher in bird colony areas,” says researcher Thomas Davidson from Aarhus University .

Analysis of the ratio of stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen were used to track the flow of the marine derived nutrients from sea to land.

“Using a mass balance model we found that at least 85% of off all terrestrial and aquatic biomass was fuelled by nutrients brought to land by the little auk,” tells Thomas Davidson.

Whilst the terrestrial ecosystem benefited from the increased nutrients that the birds bring, creating lush green landscapes and supporting many grazers, the lakes and rivers appear to suffer.

In contrast to other species that transports nutrients from sea to land, such as the Pacific Salmon, which increases aquatic productivity and biodiversity, the little auk reduced biodiversity.

The little auk guano is very high in nitrogen and not only fertilizes the systems but lowers the pH, as low as 3.4 in one lake. These very acid conditions are rather hostile for higher plants and animals, so few invertebrates and no fish are able to survive. Also the high nutrients, with few grazers able to survive means that the lakes have green water and are the greenest lakes yet recorded in Greenland.

“Our study found that the little auk acts as an ecosystem engineer across a large area of NW Greenland. The colonies stretch over a 400 km range and up to 10 km inland so a very large area if affected. This creates highly productive oases in an otherwise rather barren landscape,” says Thomas Davidson.

Contacts:

Thomas Davidson, Arctic Research Centre, Department of Biology, Aarhus University, mail: thd@bios.au.dk, phone: +4528323301

Anders Mosbech, Arctic Research Centre, Department of Biology, Aarhus University, mail: amo@bios.au.dk, phone +4587158686

Ivan González-Bergonzoni, Universidad de la República, Montevideo, Uruguay, mail: ivg@fcien.edu.uy.

Read more: http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/lookup/doi/10.1098/rspb.2016.2572

The Greenland coast of the North Water Polynya. The areas in red are the little auk colonies showing the large extent of land and fresh water affected.

Big beast on the move! Musk ox and their young grazing on the lush green landscapes created by the little auk colonies. (Photo: P. Lyngs)

A local hunter from Savvissik waits with his net for the next flock of bird to pass by. (Photo: K. Johansen)

A Little auk colony in Northwest Greenland. The birds' droppings bring nutrients from the sea as birds swarm in the air and gather on club-stones before descending to secluded nests below the stones. (Photo: P. Lyngs)